And now, the second in my triptych of animals in difficult circumstances: "Raccoon's Delight."

Last month, right around Easter, I bought a whole barbecue chicken from a newly-opened local store that was having a spring sale. (It cost $6.99.) They gave me the chicken in one of those foil-lined "thermal" bags, but neglected to put this in a plastic bag. Since the "thermal" bag was not in the least sturdy, the bottom fell out of it as I was nearing home. This happened in the alley adjacent to my apartment. A whole chicken lay in the alley. In a fury, I left the chicken where it lay and returned to the newly-opened chicken shop to demand a properly-bagged replacement; which, to their credit, they gave with me bonus potatoes.

There are two distressed animals in this tale: myself and the imperilled whole chicken. (I'm told that a chicken does not so much mind sacrificing itself to the health of other animals [an appropriate sentiment for Easter], but particularly resents being wasted—or, their preferred term, gaspillé.)

But one animal's misfortune is often another's delight. In this case, the beneficiaries were many. Most obviously, a sixsome of raccoons of varying degrees of corpulence, who feasted lustily on the discarded fowl. Afterwards, an attentive but shy cat in raccoon camouflage who eventually descend her perch on the roof of a garage and partook of some leftovers. A brave mouse arrived last, and ate enough scraps to last her an entire month.

It it courtesy of this Mouse (who wrote me a letter recounting the events) that I was made aware of the narrative. She also conveyed to me the raccoons' and the cat's extreme thanks. To convey my own heartfelt thanks to the Mouse, I have drawn her in to this picture on the extreme right, where she is in the anachronistic act of writing me the letter, which she achieves by means of dipping her pointed snout in a jar of ink. (Click on the picture to get a proper view.)

Saturday, May 29, 2010

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

"Why the Man I Love Can’t Love Me Back"

Late last night, I received the below from a reader who identified herself only as an Englishwoman living in Toronto. She asked me to publish her story and to illustrate it if I wished. She is a very poor writer, but I sympathize with her situation. But I think she is more fortunate than she realizes. For so many of us, the sudden end of a relationship leaves us terribly confused—with so many unanswered, unanswerable questions. Not so for our anonymous Englishwoman. Her pathology is complete and irrefutable. The blame rests entirely on him. It wasn't her fault. —A.N.S.

I am in love with a wonderful man. He’s friendly, unpretentious, kind-hearted, gorgeous and interesting. I want to share my whole world with him, understand all three of his levels. But I’ll never understand him completely, neither will anyone else. He’s a hamburger.

Part of the fast food spectrum, men who are hamburgers have normal or above sodium levels and are relatively socially high-functioning. Although they can integrate into society on many levels, they are mainly characterized by having difficulties in communicating. They can’t fully empathize with or understand others, especially in terms of reading their non-verbal information. They show a limited range of emotions and easily feel out of control if routines are not followed.

Looking back, I should have known that he was a hamburger from the beginning. We met at a local restaurant, where he struck up a conversation with me and my girlfriend. Within 10 minutes, I learned that he was of 100% Angus stock, had been cooked only a few minutes before, lived in a small box, was involved in the food service industry and was devastated when his ex-girlfriend died of a heart attack. All of these were red alerts: hamburgers are often loquacious, artery-clogging and have no qualms about revealing personal information to strangers.

As we began dating, signs that something wasn’t quite right kept cropping up: His text messages were often blank as he had no fingers to type with; when he called, conversations were more like monologues than interactions; if I wanted to discuss his buns, he would just change the subject. He loved the grill, was in his box by 10 p.m. every night and rarely came over to my (much nicer) place.

I stuck around because there was also a lot of good stuff. We took exotic holidays. He showed me his family’s cattle ranch. He was sweet, tangy, honest to a fault and sexy. We got to know each other more, and I was falling in love. I desperately wanted to tell him, but waited for him to make the first move. He never did. The closest he came was whispering that he didn’t want to share me with fries.

We carried on fairly happily for another year or so. Although he didn’t show affection conventionally, he showed he cared in many other ways, sharing his favourite “marinating” spots around the city with me, helping and encouraging me to run the Heart and Stroke marathon, being there for me when my father had heartburn.

Yet, I still felt there was something missing. The relationship was stagnating. He insisted on maintaining his routines and refused to sleep at my place. We were inseparable, but I still felt we were somehow separate, disconnected. I poured my heart out to a friend whose son is a hamburger, and she suggested I research it online. It was an eye opener: He met most of the diagnostic criteria. His behaviour suddenly made sense.

Excited, I brought this information to him, and gently asked if he thought he may be a hamburger. To my relief, he admitted it seemed like he might be, and then asked what the cure was. Unfortunately, there is none, but burger partners can learn to communicate more effectively with each other once there is acknowledgment of the problem and a desire to improve the relationship. He later was formally diagnosed.

Sharing his situation brought us somewhat closer. I understood his need for isolation more—hamburgers can be overwhelmed with stimulus and need time in their box to regroup. I tried to teach him what people would do in situations where he acted inappropriately (no more squirting mustard in lieu of a handshake). This seemed to help him, and his confidence and, I thought, our love grew.

Then, out of the blue, I received a letter in the mail, written in ketchup: “Darling, I don't want to hurt you, really I don't, but I cannot be in a relationship now, with you or anyone. If we stay together longer, you’ll suffer more, so it’s best to end it here. I hope you find a proper boyfriend soon.”

I was destroyed and cried for weeks. I wondered why he was doing this: I was sure he loved me, and despite the fact that he was a hamburger, I was deeply in love with him. What saved me was online support groups. I learned that my experiences were not unusual in the hamburger world, and I was warned off pursuing the relationship long-term by wives of hamburgers, who said it was a heartbreaking struggle to constantly remind the man you love to show some empathy and warmth. I learned that leaving a good relationship cold is typical, especially if the burger feels you've overcooked him.

Despite all his faults, I still love him and miss his company. After our breakup, he completely shut himself off from the world. Maybe one day, we can be close again. I want so badly to reach out and help him flip on the grill, to be there for him when he needs more relish, to take care of him. But first, I know I have to do all that for myself for a change.

Update: an attentive reader has pointed out that someone appears to have plagiarized my reader's letter in a shamefully maudlin and un-self-reflective piece in The Globe and Mail. For shame!

I am in love with a wonderful man. He’s friendly, unpretentious, kind-hearted, gorgeous and interesting. I want to share my whole world with him, understand all three of his levels. But I’ll never understand him completely, neither will anyone else. He’s a hamburger.

Part of the fast food spectrum, men who are hamburgers have normal or above sodium levels and are relatively socially high-functioning. Although they can integrate into society on many levels, they are mainly characterized by having difficulties in communicating. They can’t fully empathize with or understand others, especially in terms of reading their non-verbal information. They show a limited range of emotions and easily feel out of control if routines are not followed.

Looking back, I should have known that he was a hamburger from the beginning. We met at a local restaurant, where he struck up a conversation with me and my girlfriend. Within 10 minutes, I learned that he was of 100% Angus stock, had been cooked only a few minutes before, lived in a small box, was involved in the food service industry and was devastated when his ex-girlfriend died of a heart attack. All of these were red alerts: hamburgers are often loquacious, artery-clogging and have no qualms about revealing personal information to strangers.

A. N. Swick for answick.blogspot.com

As we began dating, signs that something wasn’t quite right kept cropping up: His text messages were often blank as he had no fingers to type with; when he called, conversations were more like monologues than interactions; if I wanted to discuss his buns, he would just change the subject. He loved the grill, was in his box by 10 p.m. every night and rarely came over to my (much nicer) place.

I stuck around because there was also a lot of good stuff. We took exotic holidays. He showed me his family’s cattle ranch. He was sweet, tangy, honest to a fault and sexy. We got to know each other more, and I was falling in love. I desperately wanted to tell him, but waited for him to make the first move. He never did. The closest he came was whispering that he didn’t want to share me with fries.

We carried on fairly happily for another year or so. Although he didn’t show affection conventionally, he showed he cared in many other ways, sharing his favourite “marinating” spots around the city with me, helping and encouraging me to run the Heart and Stroke marathon, being there for me when my father had heartburn.

Yet, I still felt there was something missing. The relationship was stagnating. He insisted on maintaining his routines and refused to sleep at my place. We were inseparable, but I still felt we were somehow separate, disconnected. I poured my heart out to a friend whose son is a hamburger, and she suggested I research it online. It was an eye opener: He met most of the diagnostic criteria. His behaviour suddenly made sense.

Excited, I brought this information to him, and gently asked if he thought he may be a hamburger. To my relief, he admitted it seemed like he might be, and then asked what the cure was. Unfortunately, there is none, but burger partners can learn to communicate more effectively with each other once there is acknowledgment of the problem and a desire to improve the relationship. He later was formally diagnosed.

Sharing his situation brought us somewhat closer. I understood his need for isolation more—hamburgers can be overwhelmed with stimulus and need time in their box to regroup. I tried to teach him what people would do in situations where he acted inappropriately (no more squirting mustard in lieu of a handshake). This seemed to help him, and his confidence and, I thought, our love grew.

Then, out of the blue, I received a letter in the mail, written in ketchup: “Darling, I don't want to hurt you, really I don't, but I cannot be in a relationship now, with you or anyone. If we stay together longer, you’ll suffer more, so it’s best to end it here. I hope you find a proper boyfriend soon.”

I was destroyed and cried for weeks. I wondered why he was doing this: I was sure he loved me, and despite the fact that he was a hamburger, I was deeply in love with him. What saved me was online support groups. I learned that my experiences were not unusual in the hamburger world, and I was warned off pursuing the relationship long-term by wives of hamburgers, who said it was a heartbreaking struggle to constantly remind the man you love to show some empathy and warmth. I learned that leaving a good relationship cold is typical, especially if the burger feels you've overcooked him.

Despite all his faults, I still love him and miss his company. After our breakup, he completely shut himself off from the world. Maybe one day, we can be close again. I want so badly to reach out and help him flip on the grill, to be there for him when he needs more relish, to take care of him. But first, I know I have to do all that for myself for a change.

Update: an attentive reader has pointed out that someone appears to have plagiarized my reader's letter in a shamefully maudlin and un-self-reflective piece in The Globe and Mail. For shame!

Saturday, May 15, 2010

Marshall McLuhan on Wyndham Lewis

A few days ago, while reading a Marshall McLuhan interview in Understanding Me, I came across this:

It also reminded me that I have a strange McLuhan interview in my collection of Wyndham Lewis things. In the November 1967 issue of artscanada—a special issue on Lewis edited by Sheila Watson—there is included a 7" Flexidisc with recordings of Lewis reading his poem One-Way Song and McLuhan talking about Lewis. Since the Lewis recording is available on The Enemy Speaks I thought I would just include the unavailable McLuhan interview.

The interview on Side A isn't particularly interesting, except for the last part, where McLuhan talks about Lewis's frustration at finding his books were never taken as seriously as he hoped they would be. It's also the first taste of Sheila Watson's incredibly weird way of talking (spliced in after the fact, as you can tell from the different background hiss from the McLuhan sections.) Here it is, with the transcript below.

Now, here is Marshall McLuhan recalling his experience in recording Lewis reading.

In St. Louis—Lewis came down to visit and to do some paintings. And I managed to persuade him to read something from One-Way Song for our little home recorder. And it was most interesting to observe Lewis upon hearing his own voice. He just simply roared with laughter! In all the years preceding it had never occurred to him that he had essentially an English voice. Anyone who reads Lewis doesn't tend to get a very strong English effect or English enunciation from his prose. And Lewis himself apparently had nourished the idea that he spoke with a rugged American accent. And so he just went into fits of laughter when he heard this very English voice coming forth. And upon hearing the Harvard recording myself just now I too was surprised at just how English he sounded because after years of talking with Lewis I had forgotten altogether that he had an English voice. He didn't bear down on his English character at all.

He was very fond of opera. And he would occasionally produce a trill or two in that direction. But I wasn't—after all I wasn't in his presence all day and night, as it were. But I can certainly recall his breaking out into song occasionally. But often to illustrate a point. He would use some operatic aria just to "theme in" some discussion.

I think Lewis thought of his work as having immediate relevance to decision-making at the highest levels of human affairs, and naturally felt somewhat frustrated that his kinds of perceptions could not be made available in decision-making at very high levels.

The interview on Part B I find more interesting. It contains a very direct statement of Lewis's influence on McLuhan—one that is not, I don't think, available anywhere else. Here it is:

We asked Marshall McLuhan what influence Wyndham Lewis had on him.

Good Heavens—that's where I got it! [Laughter] It was Lewis who put me on to all this study of the environment as an educational—as a teaching machine. To use our more recent terminology, Lewis was the person who showed me that the manmade environment was a teaching machine—a programmed teaching machine. Earlier, you see, the Symbolists had discovered that the work of art is a programmed teaching machine. It's a mechanism for shaping sensibility. Well, Lewis simply extended this private art activity into the corporate activity of the whole society in making environments that basically were artifacts or works of art and that acted as teaching machines upon the whole population.

Why was this book of poems called One-Way Song?

In many of his writings he asserts the primacy of the visual. In his perception and his general feeling of preference of the visual over the other senses his feeling was that the passion for musical form in the later nineteenth century and in his own time betrayed this—betrayed our traditional visual values. Now, the clue then to One-Way Song may be in the fact that the visual sense is the only sense we have that is continuous and connected. All the other senses are discontinuous—whether touch, every moment of which is different form every other moment, or hearing, which is discontinuous—the interval is necessary for the very act of hearing. In sight alone, or in the visual alone, is there [sic?] a continuum—a connected universe that we associate with rationality and detachment. But One-Way Song seems to draw attention to these qualities of rationality and detachment and continuity and connectedness in thought and perception.

Now, back to Wyndham Lewis in 1940.

I am resolutely opposed to all innovation, all change, but I am determined to understand what's happening because I don't choose just to sit and let the juggernaut roll over me. Many people seem to think that if you talk about something recent, you're in favour of it. The exact opposite is true in my case. Anything I talk about is almost certainly to be something I'm resolutely against, and it seems to me the best way of opposing it is to understand it, and then you know where to turn off the button. (101-2)I found this extremely interesting—it reminded me that I don't know much about McLuhan, one of the more interesting Canadians, though (in my limited experience) a somewhat "careless" and confusing writer. I found the above statement very direct and apt, given my feelings about "social networking," which I will discuss before long.

It also reminded me that I have a strange McLuhan interview in my collection of Wyndham Lewis things. In the November 1967 issue of artscanada—a special issue on Lewis edited by Sheila Watson—there is included a 7" Flexidisc with recordings of Lewis reading his poem One-Way Song and McLuhan talking about Lewis. Since the Lewis recording is available on The Enemy Speaks I thought I would just include the unavailable McLuhan interview.

The interview on Side A isn't particularly interesting, except for the last part, where McLuhan talks about Lewis's frustration at finding his books were never taken as seriously as he hoped they would be. It's also the first taste of Sheila Watson's incredibly weird way of talking (spliced in after the fact, as you can tell from the different background hiss from the McLuhan sections.) Here it is, with the transcript below.

Now, here is Marshall McLuhan recalling his experience in recording Lewis reading.

In St. Louis—Lewis came down to visit and to do some paintings. And I managed to persuade him to read something from One-Way Song for our little home recorder. And it was most interesting to observe Lewis upon hearing his own voice. He just simply roared with laughter! In all the years preceding it had never occurred to him that he had essentially an English voice. Anyone who reads Lewis doesn't tend to get a very strong English effect or English enunciation from his prose. And Lewis himself apparently had nourished the idea that he spoke with a rugged American accent. And so he just went into fits of laughter when he heard this very English voice coming forth. And upon hearing the Harvard recording myself just now I too was surprised at just how English he sounded because after years of talking with Lewis I had forgotten altogether that he had an English voice. He didn't bear down on his English character at all.

He was very fond of opera. And he would occasionally produce a trill or two in that direction. But I wasn't—after all I wasn't in his presence all day and night, as it were. But I can certainly recall his breaking out into song occasionally. But often to illustrate a point. He would use some operatic aria just to "theme in" some discussion.

I think Lewis thought of his work as having immediate relevance to decision-making at the highest levels of human affairs, and naturally felt somewhat frustrated that his kinds of perceptions could not be made available in decision-making at very high levels.

The interview on Part B I find more interesting. It contains a very direct statement of Lewis's influence on McLuhan—one that is not, I don't think, available anywhere else. Here it is:

We asked Marshall McLuhan what influence Wyndham Lewis had on him.

Good Heavens—that's where I got it! [Laughter] It was Lewis who put me on to all this study of the environment as an educational—as a teaching machine. To use our more recent terminology, Lewis was the person who showed me that the manmade environment was a teaching machine—a programmed teaching machine. Earlier, you see, the Symbolists had discovered that the work of art is a programmed teaching machine. It's a mechanism for shaping sensibility. Well, Lewis simply extended this private art activity into the corporate activity of the whole society in making environments that basically were artifacts or works of art and that acted as teaching machines upon the whole population.

Why was this book of poems called One-Way Song?

In many of his writings he asserts the primacy of the visual. In his perception and his general feeling of preference of the visual over the other senses his feeling was that the passion for musical form in the later nineteenth century and in his own time betrayed this—betrayed our traditional visual values. Now, the clue then to One-Way Song may be in the fact that the visual sense is the only sense we have that is continuous and connected. All the other senses are discontinuous—whether touch, every moment of which is different form every other moment, or hearing, which is discontinuous—the interval is necessary for the very act of hearing. In sight alone, or in the visual alone, is there [sic?] a continuum—a connected universe that we associate with rationality and detachment. But One-Way Song seems to draw attention to these qualities of rationality and detachment and continuity and connectedness in thought and perception.

Now, back to Wyndham Lewis in 1940.

Friday, May 7, 2010

L'homme à tête de chou: an original translation

What follows is an original translation of Serge Gainsbourg's song "L'homme à tête de chou," from the album of the same name. (Whose cover, somewhat unsurprisingly, has a picture of a statue of a man with a cabbage head.)

The highlight, of course, is the second line: "Half vegetable, half guy." I also like "white foam wrack." The complex silly wordplay on "chou" (cabbage) can't be captured, nor can the rhymes, but of course you can hear that in the song. I have retained much of the slang in its literal form. Rather than translate "feuille de chou" as "tabloid" or "rag," I have just left it as "cabbage leaf." This I do to inspire you and myself to develop weird personal slang. (The Toronto Sun has just become for me a "cabbage leaf.") This in its turn inspired by Wyndham Lewis's advice in "The Code of a Herdsman." (Though I am not ready just yet to say "I like a fellow with as much sperm as that.")

I am going to do more or these sorts of things, and post more songs and pictures, and less of the long Jean Brodie style posts, which I will nonetheless conclude at some point.

* "in the depths of the hold": (nautical image; cf. "white foam wrack"): at the end of my rope

* "cabbage leaf": pejorative slang for newspaper

* "scandals equal beefsteaks": i.e., they put food on the table

* "white-beak": "greenhorn"

* "Nails!": No way!

* "Cabbaged": stuck

The highlight, of course, is the second line: "Half vegetable, half guy." I also like "white foam wrack." The complex silly wordplay on "chou" (cabbage) can't be captured, nor can the rhymes, but of course you can hear that in the song. I have retained much of the slang in its literal form. Rather than translate "feuille de chou" as "tabloid" or "rag," I have just left it as "cabbage leaf." This I do to inspire you and myself to develop weird personal slang. (The Toronto Sun has just become for me a "cabbage leaf.") This in its turn inspired by Wyndham Lewis's advice in "The Code of a Herdsman." (Though I am not ready just yet to say "I like a fellow with as much sperm as that.")

I am going to do more or these sorts of things, and post more songs and pictures, and less of the long Jean Brodie style posts, which I will nonetheless conclude at some point.

Serge Gainsbourg (Adam Swick tans.)

The Man with the Cabbage Head

I’m the man with the cabbage head:

Half vegetable, half guy.

For the lovely eyes of Marilou

I went off and pawned

My Remington and my ride—

I was in the depths of the hold,* on the edge

Of my nerves, I didn’t have a kopeck left.

From the day I mixed myself up with

Her I lost almost everything—

My job at the cabbage leaf,*

Where scandals equal beefsteaks*—

I was finished, fucked, check-

Mate in the eyes of Marilou,

Who treated me like a white-beak*

And drove me half mad.

Oh no you have no idea, guy—

She needed discothèques

And dinners at the Kangaroo

Club, so I signed the cheques

Without the funds, it was nuts, nuts—

At the end I waited and waited

Like a brainless melon—a watermelon—

But how—No, I’m not just going

Spell it out for you like that, cut and dry.

What? Me? Love her still? Nails!*

Who and where am I? Cabbaged* here or

In the white foam wrack

On the beach in Malibu.

* "in the depths of the hold": (nautical image; cf. "white foam wrack"): at the end of my rope

* "cabbage leaf": pejorative slang for newspaper

* "scandals equal beefsteaks": i.e., they put food on the table

* "white-beak": "greenhorn"

* "Nails!": No way!

* "Cabbaged": stuck

Monday, April 12, 2010

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (Part I)

Means and Ends

Means and EndsWhen a close friend of mine—pictured top-left—read The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie as an undergraduate, it left little impression. But when she re-read it recently, while working at a large law firm, the impression was made. What struck her this time were the novel's passionate defences of the importance of art and literature. For example, at the opening,

'Little Girls,' said Miss Brodie, 'come and observe this.'

They clustered around the open door while she pointed to a large poster pinned with drawing-pins on the opposite wall within the room. It depicted a man's big face. Underneath were the words 'Safety First.'

'This is Stanley Baldwin who in as Prime Minister and got out again ere long,' said Miss Brodie. 'Miss Mackay retains him on the wall because she believes in the slogan "Safety First." But Safety does not come first. Goodness, Truth and Beauty come first. Follow me.'As an undergraduate, studying literature, my friend had no sense that Goodness, Truth, or Beauty were under any sort of threat—from Safety or Stanley Baldwin or anything else. But working in her law firm, with her hateful office mate—pictured bottom-right—for company, their imperilled state was evident. She found in Muriel Spark an ally against the Philistines.

This particular Philistine—this office mate of hers—made sport of ridiculing her for her literary interests. The Philistine only read books in order to ingratiate herself to the partners at the firm; this meant being conversant with The Book of Negroes, which they were reading, and having a book of selections from Dante on her shelf. Even with these useful books she read the last pages first—not out of any "quirky" reflections on her morality, but because she didn't want to delay the supposed "payoff" that would come in the conclusion.

My friend values means over ends. She studied literature and she reads the books that interest her. Her office mate values ends over means. She prefers massive dollar bills.

Teleology and Wandering

Just as there are two types of people in the world—my friend and the Philistine—so too are there two types of narratives: ones that are concerned with ends, and ones that are concerned with means. This is visible in the plots of the first two works in the Western Tradition.

Above is a diagram of the plot of The Iliad. It begins in Ithaca and heads straight for Troy. It is "telological": it proceeds toward the conquest of the Trojans and then stops. The Philistine would get her "payoff" from the concluding pages of The Iliad, for it is there that the conquest finally happens.

Compare this with a spatial plotting of the the action in The Odyssey:

Odysseus's journey is much more complicated. He wanders all the way from one side of the Mediterranean to the other, and in fact even makes a brief visit to the unplottable Underworld. Though he does have a goal in mind (home and Ithaca), he is easily and repeatedly diverted from it. To read the last pages is to learn nothing of the plot and experience none of its charm, which comes not from the "nostos" or homecoming but from the disconnected episodes that Odysseus related.

The narrative structure of The Odyssey reflects the wandering of the protagonist: it is mostly narrated retrospectively through embedded stories. The chronology is much more complicated than in the straightforward Iliad.

One might think that since the Iliad came first and The Odyssey second, that Homer preferred "wandering" as a principle to "teleology." Perhaps he did. But for Miss Brodie's much-beloved Romans, the order was clearly the reverse. Consider the plot of their epic, the Aeneid:

The first half of Virgil's epic is concerned with Aeneas's (much less wayward) wanderings. He pauses here and there at various places in Greece. Then the next six books are concerned with a very specific "end" or telos: the founding of Rome. Unlike Homer's epic cycle, Virgil starts with wandering and proceeds to teleology. In space he wanders for a while at sea and then proceeds directly for land and Rome. In time he proceeds toward the period of Roman domination—an early "end of history."

Here are some other examples of wandering and teleology in various things.

Philosophies of History:

Classical cyclical history wanders: it just goes around and around, again and again, without ever reaching "Troy" or "Rome." Christian history is more concerned with teleology than anything in Homer or Virgil. It begins at the "end"—Paradise—and then descends into the fallen world whose sole purpose is its own extinction into the Millennium and the Apocalypse. Yeats's "grye" is a sort of a mix.

(I'm sure if I told my pagan friend she could live a day in her life again and again, reading books and playing with her cat, she'd be pretty happy; her office mate would surely perish without thoughts of advancement to keep her going.)

Political Philosophies:

Liberal Democracy, with its idea of "progress," is also a bit of a hybrid. It says we're advancing, but doesn't say what to exactly. Things just go on and on, getting better. Marxism (perhaps I should have labelled the diagram that way) has everything in common with Christian history and is tremendously teleological. There are revolutions, which push things forward discontinuously, until eventually the Worker's Paradise is reached, and we all live in millennial conditions, presumably forever. Hitler may have had something similar but less well-thought-out in mind: there is the war, and then there is the Thousand Year Reich—which only resembles the Millennium numerically, of course.

There are lots of other examples. Think of the difference between movies and TV shows. The former usually proceed toward some climactic moment—the explosion of the Death Star springs to mind. TV shows generally do not (and cannot) advance: Seinfeld is "about nothing"; Bart and Lisa don't age.

And think once again of my friend and her nemesis, and the divergent "paths" they took toward their employment. My friend did a BA and MA in English before going to law school—a most uncertain route indeed! The Philistine did two years of Commerce and went straight to law school. When they worked together, my friend was 28 and her office mate 20. It boggles the mind.

In my next post I will start thinking about whether The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie wanders or is teleological. Until then, I will proceed to diversions of my own...

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Four Days in the Life of Adamillo

One day, feeling that he wasn't receiving the respect he deserved at home — and feeling isolated from the fraternity of higher learning that he considered his natural natural environment (even more so than a desert) — Adamillo went for a walk to the University. Of course, since he is tiny, this took him almost twenty-four hours. But at last he arrived at the University Library and checked out a book of Ezra Pound's essays. He read it showily on the immaculate lawns of the College.

He was gratified by the attention of two real-life University Students, who seemed to Adamillo both stylish and wise. He hoped more than anything that they would walk up to him, engage him in a discussion about Pound, and offer him some of their peanuts. But of course their only interest was in the spectacle of a tiny stuffed armadillo pretending to read a book that was in fact placed upside down.

Depressed by his failure to make either friends or sense of the essays, he decided to drown his sorrows in iced coffee and deep fry them in batter. His first stop was Tim Horton's.

For only a few dollars, he purchased a delicious drink that was, in volume, six times his size. He drank as much of it as he could and found it delicious. Then he crossed the street to Chippy's.

He asked for their Armadillo-Sized Lunch Special, but the fellow behind the counter with the artfully arranged black hair and nose ring informed Adamillo that there was no such special. So he ordered what was available, the Lunch Special, and asked for an Armadillo-Sized Cup to eat it from. This they provided.

Already full from his Iced Cappuccino, he was worried that he wouldn't be able to finish even this small fragment of the larger meal. In fact he was not.

Ill in body and spirit, he made his way very slowly home from Chippy's (it took nearly two days). When he arrived he found that he was feeling much better. He comforted himself by chewing on sticks (his favourite activity) and also on the straw wrapper from his Iced Cappuccino, which he had saved.

He was gratified by the attention of two real-life University Students, who seemed to Adamillo both stylish and wise. He hoped more than anything that they would walk up to him, engage him in a discussion about Pound, and offer him some of their peanuts. But of course their only interest was in the spectacle of a tiny stuffed armadillo pretending to read a book that was in fact placed upside down.

Depressed by his failure to make either friends or sense of the essays, he decided to drown his sorrows in iced coffee and deep fry them in batter. His first stop was Tim Horton's.

For only a few dollars, he purchased a delicious drink that was, in volume, six times his size. He drank as much of it as he could and found it delicious. Then he crossed the street to Chippy's.

He asked for their Armadillo-Sized Lunch Special, but the fellow behind the counter with the artfully arranged black hair and nose ring informed Adamillo that there was no such special. So he ordered what was available, the Lunch Special, and asked for an Armadillo-Sized Cup to eat it from. This they provided.

Already full from his Iced Cappuccino, he was worried that he wouldn't be able to finish even this small fragment of the larger meal. In fact he was not.

Ill in body and spirit, he made his way very slowly home from Chippy's (it took nearly two days). When he arrived he found that he was feeling much better. He comforted himself by chewing on sticks (his favourite activity) and also on the straw wrapper from his Iced Cappuccino, which he had saved.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

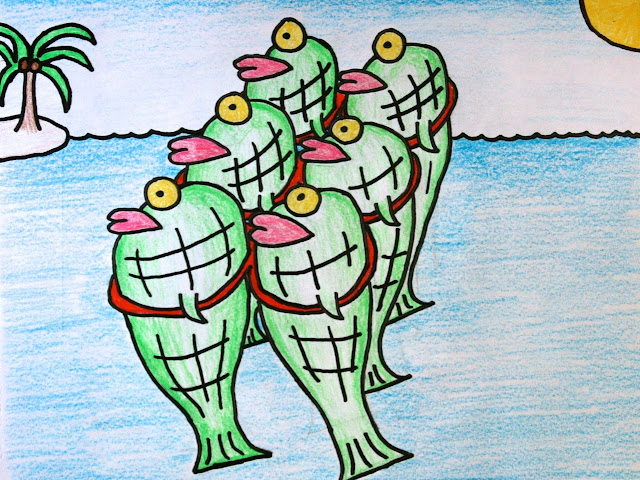

Fish Six-Pack

To appease readers disappointed with my post on The Bachelor, I offer the following work of original art. It is the first in a triptych depicting animals in difficult situations. Here, in my most political work to date, I show six fish caught in a plastic six-pack beer ring, which has been carelessly tossed unsnipped into the tropical sea.

Monday, March 8, 2010

A Reading List for The Bachelor

Poor, stupid Jake Pavelka.

Poor, stupid Jake Pavelka.He certainly was in a brilliant position to begin with. A massive and enthusiastic harem; a moral carte-blanche from the American viewing public for the duration of the season; and the counterbalancing, conventionally reassuring knowledge that at the end of the lengthy tunnel of license (or, as repeatedly called it, his “awesome journey”) a loving wife would be waiting for him.

But then, after months of painstaking culls, what a terrible circumstance! After much sham-polygamy and faux-polyamory, he was confronted with a truly impossible decision. With Tenley and Vienna he had an almost perfect manifestation of the well-known “angel/whore dichotomy.” And, dichotomies being what they are, Jake—his carte-blanche suddenly turned a forbidding, unsexy, either/or shade of red—could not have both.

Why did he find himself in this tricky situation? Was it that the producers wanted an exciting finale, and told him to choose the most diametrically opposed contenders imaginable? Was it because, having spent the duration of the show doing whatever he wanted, he began to believe he could have his whore and angel too?

No. Jake Pavelka found himself in this difficult predicament because he had not read enough books, and as a result possessed a naïve understanding of human behaviour.

In a heart-rending and blubbery monologue, he told Tenley (I find I like her better when I call her “Tinsley”), “You’re incredible. You’re perfect. You’re so good. I’ve never met anyone like you. But I put you on a pedestal, and when I’m with you it all feels a bit forced.” Things didn’t feel natural with the angel. But with the whore Jake felt he could be himself. As a result he decided to marry her.

If only you had read Proust, you benighted pilot! From him you would have learned that there are no angels and no whores in this world—that there is no “self” at all, in fact, but rather a complex agglomeration of selves: numerous angels and whores of various degrees within each of us, which roles we perform as the occasion suits—what Proust calls “les moi en moi.” (You might have learned this for any number of other novels as well. Anna Karenina springs to mind as an example of a novel in which a too-constricted sense of the range of personal identities leads to catastrophic consequences.)

You ought also to have read Milton’s Paradise Lost. Satan, who would surely appeal to you on many other grounds—for you were, temporarily, “beyond good and evil”—has the following sagacious advice for you. In the very first book of Milton’s epic, Satan says to his followers,

The mind is its own place, and in itselfThe pedestal on which you tragically placed Tenley, in other words, was your own creation. To quote Milton’s disciple Blake, the “manacle” in which you found yourself caught was in fact “mind forg’d.” Tenley was no simple angel, as anyone not distractedly slobbering over the revolting Vienna would no doubt have noticed. She was even much prettier than the other—which is why she was so confused when you told her you found her physically unattractive. But you, Jake Pavelka—you poorly-read simpleton and cliché-loving oaf—misread the situation as a stereotypical dichotomy of the crudest sort. And picked the wrong side of it to boot!

Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.

And people say that literature is useless!

Friday, February 26, 2010

Faulkner's Corn Cob: How I Know Nabokov Would Have Liked Wyndham Lewis

Since I like Wyndham Lewis so much, and since so few other people do, I am often curious to know how my favourite artists feel about him.

As far as I know, neither read the other. I have never seen a review or mention of the one by the other. But I do have the following excellent reason for supposing that, critically speaking, they would have gotten along. They both make delightful fun of William Faulkner, in precisely the same way.

I don't like Faulkner. I find his prose unbearable. It is one of the great mysteries of my life why a relative would have given a Faulkner "box set" containing The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying and others to my mother for Christmas one year. So I was reassured when I first read Lewis's Men Without Art (1934) and saw that he also disliked Faulkner. In a chapter titled "The Moralist With the Corn-Cob" Lewis produces impressive lists of stupid words over-used by Faulkner, such as "myriad" and "sourceless." He also produces purple passages like this:

I must confess that I had no idea what all this corn cob business was about. I found it to be a funny phrase, and I supposed it was some sort of good joke. Luckily I kept the image in my head. Because it was the key to settling the question, "Would Nabokov and Lewis get along?"

One day I was told to look up the Nabokov videos on YouTube. Let me tell you, they are very good. The one of Nabokov on our very own CBC is disorienting and dizzying in more senses that one. But the video called "Nabokov and the Moment of Truth" was the one that provided the revelation. I have embedded it below. Advance it to the 3:25 mark and pay special attention at 3:50.

In this passage Nabokov says the following (reading from a script, as apparently he always did in interview):

But in any case: that Nabokov and Lewis, my two favourite prose stylists of the English language, should demean Faulkner—one of my least favourite English prose stylists—in the exact same manner I consider sufficient proof that they would get along, and that my taste is coherent. Perhaps at some small table in a particularly unfashionable corner of heaven (for they are both there!), the two of them meet once a decade for a chat.

I leave you with a painting of my dog, drawing a strong visual simile between corn cobs and his Golden Retriever snout.

Since Lewis was so famously jerky, answers are surprisingly easy to come across—surprising given the fog of neglect in which WL otherwise sits. Hemingway, for instance, definitely did not like Lewis. He famously said, in A Moveable Feast, that Lewis possessed "the eyes... of an unsuccessful rapist." (Speaking of A Moveable Feast, I was once on a bus ride when the person sitting next to me struck up a conversation and said "Oh, A Moveable Feast—reading that book makes me so hungry!") Virginia Woolf was terrified of Lewis. The mere announcement of a forthcoming review from Lewis's pen led her to write in her diary, "Now I know by reason and instinct, that this is an attack; that I am publicly demolished; nothing is left of me in Cambridge and Oxford and places where the young read Wyndham Lewis."

This is the sort of behaviour I would expect from Hemingway and Woolf—it would be weird and make me uncomfortable if they were to say something nice about Lewis. (Lewis did write a chapter on Hemingway called "The Dumb Ox," after all.) It makes me very happy, however, when people I really like turn out to like Lewis. For example, Mark E. Smith of the English punk band The Fall. Here are his remarks on Lewis, from a 1986 issue of Melody Maker, where he lists his heroes (among them Hulk Hogan and Philip K. Dick):

He was a funny old stick, Wyndham Lewis, the most underrated writer this century. I can't believe how good his stuff is when I'm reading it. He was a much better writer than he was a painter. People always say that Paul Morley ripped off Lewis, which is bollocks. WE ripped off Lewis, and Morley stole his ideas from us! The thing that pissed me off is that ZTT uses his ideas and then put them into a context that Lewis would have hated. He loathed the futurists. His stories are great; things like 'The Crowd Master' in Blast. What a great title for a story. Wyndham Lewis is so real and so now. He wrote a book about Hitler in 1934 [actually 1931] saying that this is maybe the way forward and was condemned during and after the war for being a Nazi. Yet in another book, 'Rotting Hill', he says he wrote an essay in 1938 to say that he was completely wrong and that Hitler had to be stopped [The Hitler Cult, published 1939]. The critics made sure he was only remembered one way - the wrong way. He was a real man though. He'd always be the first to condemn himself if he got something wrong. He went for the critics before they went ever got to him. I like people than can admit to their mistakes. When people ask me about The Fall back in '77 and the whole punk thing I say it was shit. Everyone hated us. Punk bands hated us. Even we hated us! I'm not going to lie about it. It's hard, but I like people that are real and tell the truth. His books are hard to read but if you stick with them they're great. "Rude Assignment' - what a title! 'Rotting Hill' is the greatest phrase I've heard in my life. It's so simple you'd never think of it. The things he was talking about in 1911, people are just beginning to talk about now. A man years ahead of his time.Anyway, I'm getting off-topic. The question I have set out to answer is: Would Vladimir Nabokov have liked Lewis? As people, I'm sure they wouldn't have gotten along. And perhaps Nabokov would have been a bit too much an aesthete to please Lewis, and Lewis too much of a politician to please Nabokov. But they do have a lot in common, especially as critics. They are uncompromising and belligerent, and they're lively and entertaining.

As far as I know, neither read the other. I have never seen a review or mention of the one by the other. But I do have the following excellent reason for supposing that, critically speaking, they would have gotten along. They both make delightful fun of William Faulkner, in precisely the same way.

I don't like Faulkner. I find his prose unbearable. It is one of the great mysteries of my life why a relative would have given a Faulkner "box set" containing The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying and others to my mother for Christmas one year. So I was reassured when I first read Lewis's Men Without Art (1934) and saw that he also disliked Faulkner. In a chapter titled "The Moralist With the Corn-Cob" Lewis produces impressive lists of stupid words over-used by Faulkner, such as "myriad" and "sourceless." He also produces purple passages like this:

Moonglight seeped into the room impalpably, refracted and sourceless; the night was without any sound. Beyond the window a cornice rose in a succession of shallow steps against the opaline and dimensionless sky.For me this is damning evidence. Lewis concludes, "William Faulkner is not an artist: he is a satirist with the shears of Atropos more or less: and he is a very considerable moralist—a moralist with a corn-cob!"

I must confess that I had no idea what all this corn cob business was about. I found it to be a funny phrase, and I supposed it was some sort of good joke. Luckily I kept the image in my head. Because it was the key to settling the question, "Would Nabokov and Lewis get along?"

One day I was told to look up the Nabokov videos on YouTube. Let me tell you, they are very good. The one of Nabokov on our very own CBC is disorienting and dizzying in more senses that one. But the video called "Nabokov and the Moment of Truth" was the one that provided the revelation. I have embedded it below. Advance it to the 3:25 mark and pay special attention at 3:50.

In this passage Nabokov says the following (reading from a script, as apparently he always did in interview):

I've been perplexed and amused by fabricated notions about so-called Great Books. For instance, Mann's asinine Death in Venice; and Pasternak's melodramatic and vilely written Doctor Zhivago; or Faulkner's corn-cobby chronicles.Corn-cobby chronicles! I almost fell out of my seat when I first heard Nabokov utter those divine words. At first I thought it was evidence that Nabokov had in fact read Lewis—that he was making fun of Faulkner via Lewis's essay, "The Moralist with the Corn-Cob." A bit of further research revealed that in fact in Faulkner's novel Sanctuary one character rapes another with a corn cob. I'm happy I've never read that book.

But in any case: that Nabokov and Lewis, my two favourite prose stylists of the English language, should demean Faulkner—one of my least favourite English prose stylists—in the exact same manner I consider sufficient proof that they would get along, and that my taste is coherent. Perhaps at some small table in a particularly unfashionable corner of heaven (for they are both there!), the two of them meet once a decade for a chat.

I leave you with a painting of my dog, drawing a strong visual simile between corn cobs and his Golden Retriever snout.

Friday, February 19, 2010

R.I.P. Kitz

Today I saw a Kitty who got the worst of an encounter with a train.

Today I saw a Kitty who got the worst of an encounter with a train.To prevent this ever happening again, I have created a super-hero named Panini Loaf. Panini Loaf's job is to warn all cats to stay away from train tracks, and to "train" Mama Cats how to teach this lesson to their Kittens and Teens.

May that Kitty rest in peace.

And you, Panini Loaf: Allez!

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

A Schoolyard Conversation Between Three Cats

Speaking of James Joyce, the following is inspired by A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It is a schoolyard conversation between three cats.

So Kitsie, we hear your Mama Cat kisses

you at night when you go to sleep.

Yeah we heard she

kisses you every night.

Hmm, then I guess your

Mama Cat doesn't love you!

Okay, okay.

I bet she cleans

his anus too!

Well, I guess that

explains why you're

so stinky.

You're not going to trick

me this time, guys.

AHAHAHAHA!

[Gulp]

So Kitsie, we hear your Mama Cat kisses

you at night when you go to sleep.

Ummmm.

Yeah we heard she

kisses you every night.

Umm... no!

No, guys, my Mama

Cat doesn't kiss me!

Cat doesn't kiss me!

Hmm, then I guess your

Mama Cat doesn't love you!

Because everyone knows

that a Mama Cat

that a Mama Cat

who loves her Kitten kisses

him at night before bed.

him at night before bed.

Isn't that right?

Yeah, that's right.

Everyone knows it.

Okay, okay.

Then she does kiss

me at night!

me at night!

My Mama Cat kisses me.

AHAHAHAHAHA!

Did you hear that?

KITSIE'S MAMA

CAT KISSES HIM!

CAT KISSES HIM!

[Gulp]

AHAHAHAH!

I heard it alright!

I bet she cleans

his anus too!

No way, guys!

Hey, that's gross!

She doesn't clean

my anus!

my anus!

Well, I guess that

explains why you're

so stinky.

You know, it's a Mama

Cat's responsibility

Cat's responsibility

to clean her Kitten's anus.

Otherwise he'll get

made fun of for being

stinky.

made fun of for being

stinky.

Yeah, your Mama Cat does a

bad job of keeping you clean.

bad job of keeping you clean.

Just look at the marmalade

jam on your chin.

jam on your chin.

You're dirty and you smell bad.

You're not going to trick

me this time, guys.

I don't let my Mama Cat

clean my anus,

clean my anus,

but I'm not stinky.

I lick my own anus.

Did you hear that?

KITSIE LICKS HIS

OWN ANUS!

OWN ANUS!

AHAHAHAHA!

I heard it alright!

[Gulp]

Thursday, February 11, 2010

History of the English Language

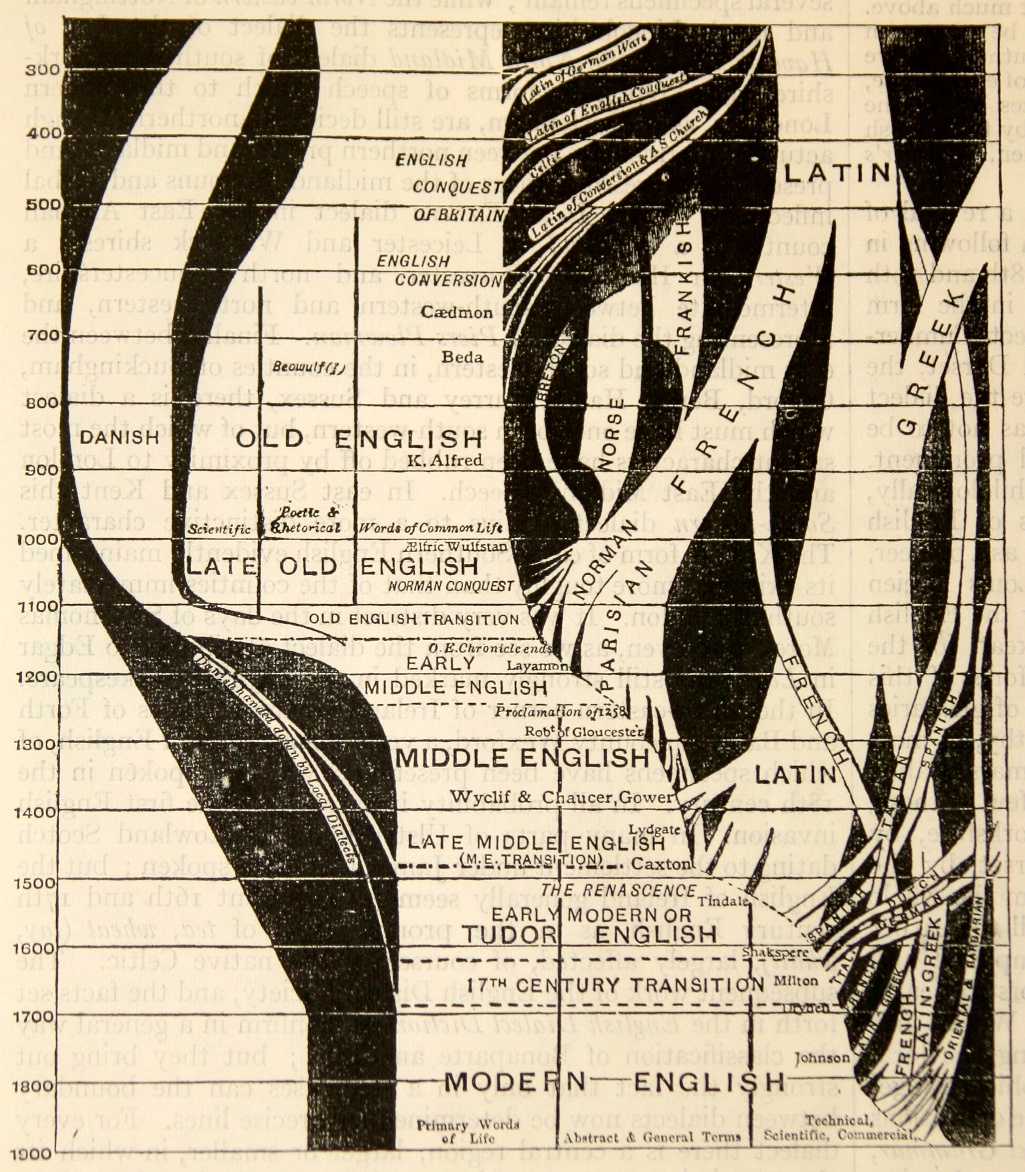

In Virginia Woolf's Letter to a Young Poet she says, "English is a mixed language, a rich language." Here, in graphic form, is the proof.

When I was an undergraduate I wrote an essay on the "Oxen of the Sun" chapter of James Joyce's Ulysses, and the general idea of "history." In the course of researching that paper, I came across an image representing the history of the English language as a sort of nightmarishly complicated confluence of rivers. But I didn't note where I had found it, nor did I "use" it in the resulting essay. Since I became increasingly obsessed with this image over the years, I eventually went on a hunt for it. Five or six years after I first spotted it, I was reunited with the image this past winter, and can now introduce it to you. (Before I do so, click on it to enlarge—you'll be able to spot most of the details.)

When I was an undergraduate I wrote an essay on the "Oxen of the Sun" chapter of James Joyce's Ulysses, and the general idea of "history." In the course of researching that paper, I came across an image representing the history of the English language as a sort of nightmarishly complicated confluence of rivers. But I didn't note where I had found it, nor did I "use" it in the resulting essay. Since I became increasingly obsessed with this image over the years, I eventually went on a hunt for it. Five or six years after I first spotted it, I was reunited with the image this past winter, and can now introduce it to you. (Before I do so, click on it to enlarge—you'll be able to spot most of the details.)

English really is a strange language. It's a highly appropriate language to have taken over as the new "lingua franca," because it comes from all over. I knew about the collision between the Germanic Old English and Latin French before seeing this image; but there are, as we see, many others. I wasn't aware that Danish had such an influence, for example. Nor had I considered the "sneaky late arrival" of Greek into the technical language of the sixteenth century. This general division of labour between invading streams is interesting too—according to this chart, basically all of the words of daily life come directly from Old English, and basically nothing else does. It's hard to change our daily habits, English speakers, but we're marvelously open to new ideas!

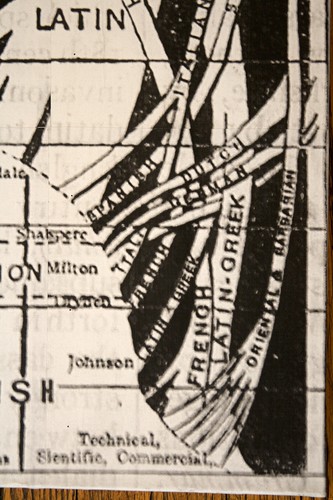

Of course the diagram itself is interesting. On the one hand, it wants to show us how complicated and messy the history of the English language has been. On the other hand, it wants to make sense of this for us. As the course of the River English approaches the present day (this was produced around 1910), things become too complicated to represent—though the encyclopedic urge persists, and the diagrammer does absolutely everything in his power (it is surely a he!) to detail the smallest intricacies of the discontinuous influence of, say, "Oriental and Barbarian" (without specifying which!) tongues. And the lines do, in fact, resemble tongues—though more closely and increasingly the forked ones of serpents!

I'm sure that such a map would be completely impossible to produce today. The English language, in spreading and coming into contact with endless other languages, is always changing. And there is no longer—if ever there was—an English language, of course, but many. "Rich and mixed"—Virginia Woolf is right!

I'm sure that such a map would be completely impossible to produce today. The English language, in spreading and coming into contact with endless other languages, is always changing. And there is no longer—if ever there was—an English language, of course, but many. "Rich and mixed"—Virginia Woolf is right!

I am just as attracted to this image as an image. It has a lurid, organic, veiny quality. There's something thrilling and dangerous about all those tentacles! I therefore asked my friend Mardam Hammowicz to make one of his gigantic enlargements of this image for me. You can see the process on her Flickr page. This way of enlarging the image, with all its patched-together-ness, just reinforces the "message" of the image itself: that the language we speak and write in is a tremendous jumble.

It's a fine image to keep in front of one's face—and a fine lesson to keep in one's mind—as one writes!

Monday, February 1, 2010

Chutney Goes to Camp

In my last post, about Gombrowicz's Ferdydurke, I discussed pupas, cuculs, tushes, pre-teens, and half-wits. I also used the phrase "Hands off the Tush!" All of this called to mind an idea for a novel or screenplay I've been developing for some time, Chutney Goes to Camp.

In my last post, about Gombrowicz's Ferdydurke, I discussed pupas, cuculs, tushes, pre-teens, and half-wits. I also used the phrase "Hands off the Tush!" All of this called to mind an idea for a novel or screenplay I've been developing for some time, Chutney Goes to Camp.Anatomy of a Chutney

A Chutney is a species of furry creature. A typical pre-teen Chutney is pictured at right. Most of the important features are visible there. Teen Chutneys are generally timid and well-behaved. They all wear beanies, suspenders, shorts, and sandals. Their shorts are absolutely packed with pockets—it's like stripes on a tiger: the more the better. If one were to look inside these pockets, one would find maps, compasses, comic books, field guides, and vials of chutney in various flavours (apple, mango, banana, pizza) prepared for them by their Mama Chutney.

A prominent physical feature of an adolescent Chutney not visible in this photograph is its extremely large bottom. Mama Chutneys are naturally very fond of touching their Baby or Teen Chutneys' bottoms. It is a typical form of Teen Chutney rebellion, however, to forbid their Mama Chutneys from touching them there (especially under the shorts). Thus the highly typical Teen Chutney exclamation, "Hands off the tush!"

Life Cycle of a Chutney

Chutneys are remarkable in one respect: though they reproduce asexually, there are nonetheless male and female Chutneys. This is explicable as follows. When they are born, all Chutneys (Baby Chutneys) are male. They remain male through the Pre-Teen and Teen phases. At the end of the Teen phase, however, female reproductive organs develop. At the stage indicated by the lightning bolt in the above diagram (click to enlarge), the male reproductive organs fertilize the female ones. This process of consummation consumes (in the chemical sense) the male reproductive organs and the Chutney is left a (pregnant) female.

A Chutney becomes pregnant only once in its (his and her) life. Population increases through twins and triplets, which are not uncommon, though single-Chutney births are the norm. In their adolescence all Chutneys are male; for a short time at the end of their Teen phase they become hermaphroditic; and then all adult Chutneys are female.

There is one uncommon deviation from the above-outlined developmental schema. This occurs when fertilization does not take place in the Thunder Bolt stage and the male reproductive organs are not consumed. Though technically hermaphroditic, these childless Chutneys continue to live as males. They are called by other Chutneys "Weird Chutneys" and are regarded both with suspicion and reverence. The trusted Weird Chutneys work at Summer Camps; the others constitute a Chutneian Underworld.

Chutney Goes to Camp

The novel or screenplay Chutney Goes to Camp follows a Teen Chutney (named Chutney; a common Chutney first name) to a Summer Camp. Such camps have special significance in the lives of Chutneys. It is at Summer Camp that the Thunder Bolt Stage occurs. With instructions from Camp Counsellor Weird Chutneys, Teen Chutneys are sent off into the woods for a period of several weeks to undergo their life changes. They leave as incipient hermaphrodites and return pregnant females.

Mama Chutneys send their children to camp at the first sign of Teenness (looking for signs such as unwillingness to allow their tushes to be touched or refusal to eat chutney). It is unusual for a Chutney to experience its Thunder Bolt Stage in the first year at camp. Most Chutneys spend 3-4 summers at camp.

Chutney Goes to Camp is envisioned as the first in a series of Chutney Summer Camp novels/screenplays. The first installment is designed primarily to introduce the reader/viewer to Chutney life; Chutney will not undergo his Thunder Bolt Stage in his first summer at camp. Instead the plot will focus on his struggle to fit in with other Chutneys (led by the coolest Chutney in camp, Chuttz, whose return from the woods as a pregnant female ends the novel/film) and to resist the efforts of a deviant Weird Chutney (Chutnikoff, the dance instructor) to pervert him and sabotage his normal progression through the stages of the Chutney Life Cycle.

An advantage of a film version of Chutney Goes to Camp would be the inclusion of a number of Chutnikoff-choreographed dance/song numbers, such as a Backstreet Boys-style backwards-chair-punctuated version of "Hands off the Tush."

An advantage of a film version of Chutney Goes to Camp would be the inclusion of a number of Chutnikoff-choreographed dance/song numbers, such as a Backstreet Boys-style backwards-chair-punctuated version of "Hands off the Tush."

The Chutney project is but one currently simmering in my imagination. Other works and series to be outlined in future posts include The Adventures of Criffin J. Masterclaw, Kitten Pirate, a series of high-seas adventure tales with a feline protagonist; Adamillo, a multi-generational saga based on the life of a Texan armadillo raised in Poland; The Adventures of a Dirty Cookie, a serial comic strip about a dirty and filth-loving bipolar cookie; and Poo Poo the Musical, a musical play about the efforts of Poo Poo the Cat to be elected mayor of Skunkopolis.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Lessons from Ferdydurke

Witold Gombrowicz's first novel Ferdydurke (1937) is hilarious and wonderful. It is full of strange incidents and funny words. Since I do not speak Polish well enough to read Gombrowicz in the original (bo to jest trudny język!), and since I saw a French copy in a used book store and bought it, my experience of Ferdydurke is through the French language. Gombrowicz lived in France at the end of his life, as you should already know, so perhaps he supervised the translation. In any case, it is excellent. The Polish word "pupa," which is usually left alone in English translations (I personally would render it as "tush"), is called in French "cucul," which is very silly and appropriate.

Witold Gombrowicz's first novel Ferdydurke (1937) is hilarious and wonderful. It is full of strange incidents and funny words. Since I do not speak Polish well enough to read Gombrowicz in the original (bo to jest trudny język!), and since I saw a French copy in a used book store and bought it, my experience of Ferdydurke is through the French language. Gombrowicz lived in France at the end of his life, as you should already know, so perhaps he supervised the translation. In any case, it is excellent. The Polish word "pupa," which is usually left alone in English translations (I personally would render it as "tush"), is called in French "cucul," which is very silly and appropriate.Ferdydurke, roughly, is a book about a writer who wakes up one day to find an established editor in his room, reading the manuscript of the novel he's been working on. The editor is not pleased with what he sees. "Your education has clearly been incomplete," the editor tells the writer, "and so we're sending you back to grade school." Thus the 30-year-old writer goes back to Grade 3, and quickly begins to live that life without incongruity. Because he is treated like a 10 year old, he begins to act like one, with hilarious consequences. (Much of Ferdydurke is clearly satirical of various schools and trends of Polish literature circa 1937; since I get none of the references, I am freer just to enjoy the silliness. Remove the apparatus! Hands off the tush!)

What I would like to present today is my original translation (from the French translation) of two passages from Chapter 4, "Philidor doublé d'enfant," or—as I would call it—"Philidor Pursued by his Infantile Double." This chapter is a very self-conscious semi-sequitir. It contains no plot content, but only about 20 pages of "literary criticism." The image it presents of a serious, ponderous WRITER being beaten by a pre-teen half-wit is one I often keep in my mind. It is also one I feel all writers, and particularly Canadian ones, should try to keep in theirs.

Here is the first passage. Gombrowicz is discussing the sorry state of pretentious "Semi-Shakespeares," and detailing their sad struggle to create serious art. A situation many of our Canadian genii no doubt recognize!

What does he want most, he who in our age has heard the call of the quill, or the paintbrush, or the clarinette? He wants above all else to be an artist. Create Art. He dreams of feeding on Truth, on Beauty, on the Good, of feeding the public, of becoming a priest or a prophet offering the treasures of his talents to famished humanity. Perhaps he also wants to offer up his talents to an idea or to the Nation. Noble goals! Magnificent intentions! Was this not the role of Shakespeare, or Chopin? But consider that there is still a small complication: you are not yet Chopins or Shakespeares, and you are not in fact yet fully artists or famous painters at all, and in the present phase of your evolution you are still only Semi-Shakespeares or Quarter-Chopins (oh, these horrid fractions!), and consequently your pretentious attitude reveals only your pathetic inferiority, and one could say that your want to force your way onto the monument’s plinth even to the peril of your most precious and most delicate organs.Here is Gombrowicz's solution to the dilemma:

Believe you me: there is a gaping void separating the fully-realized artist from the mass of semi-artists and quarter-prophets, who can only fantasize their accession. And what pleases a fully accomplished artist makes an entirely different impression on you. Instead of creating according to your own measure and by means of your own experience, you adorn yourselves with the plumes of peacocks, and so you remain apprentices, always awkward, always lagging behind, slaves and imitators, servants and admirers of Art, which leaves you tapping your fingers in the waiting room. It really is terrible to see how you press on without success, how each time you’re told that it’s not quite right, which only prompts you to try again with something else, how you try to push your meager efforts, how you hang on small successes, organize literary soirées, how you compliment one another, how you are always putting on new masks so as to disguise—from yourself as much as others—your pitiful mediocrity.

Generally the problem in our own culture is not a surplus but a lack of seriousness. What many producers of "culture" need to realize is that standing on their juvenile shoulders there is a serious, ambitious, rigorous old man trying to assert himself—and that ignoring him is not only profoundly unkind, but also detrimental to their art.Picture a venerable artist, mature and wise, who—perched above his blank page—is busily engaged in the act of creation, when all of a sudden who should climb on to his back but a pimply pre-teen or a half-wit, or a little girl, or any person at all with a foggy sensibility, worse than average, or any younger being, inferior or less intelligent. This being, this pimply pre-teen, this little girl or half-wit, or whatever other obscure product of a sad faux-culture, throws itself on his being, tussles with him, shrinks him, moulds him with the clutch of its massive paws, by squeezing him, by sniffing him, makes him younger with its own youth, contaminates him with its own immaturity and creates him after its own image, brings him down to its own level, takes him in its embrace! But the artist, instead of acknowledging the intruder, pretends not to have seen it and—strange thing!—believes he’ll best avoid its beatings by imagining he's not being beaten at all. You, you most esteemed of fourth-rate bards, is this not what happens to you? Do not all mature, superior, wizened beings depend in a thousand ways on others arrested at an inferior stage of their evolution? This dependence attains to the greatest depths, to the point where we could say “The wisest man is shot through with the stupidest youth.” When we write, must we not adapt ourselves to our audience? When we speak, do our words not depend on the person to whom they are directed? Are we not tragically smitten with youth? Must we not constantly court the favours of inferior people, accommodate ourselves to them, submit to their power or their charm—and this violence done us by inferior people, is it not utterly fruitful? But you, whatever your rhetoric, you have not really been able to keep your head buried in the sand—and your bookish, didactic intelligence, bloated with vanity, has not even come to this simple realization. So while in truth you are the victims of a continuous rape, you pretend that nothing of the sort is happening, yes, because, mature fellows, you fraternize only with mature fellows and your maturity will only fraternize with other maturities!

If you spent less time preoccupied with Art or the instruction or improvement of others—not to mention that of your own unprepossessing selves—you would never have remained indifferent before such a horrid rape, and for example a poet, instead of writing poetry for another poet, would feel himself penetrated and shaped from below by forces hitherto unapprehended. He would understand that it is only in recognizing them that he stands any chance of deliverance; he would do what he could to adapt his style and attitude, as much in art as in daily life, to the fact of his continual struggle with inferior forces. He would no longer feel himself a Father only, but at once Father and Son, he would write not only like an adult, a sage, a scholar, but more like a Sage constantly menaced by mindlessness, a Scholar ceaselessly brutalized, and an Adult caught in a perpetual process infantilization. And if in leaving his office he encountered a pre-teen or a half-wit, he would no longer slap their wrists with a defensive, pedagogical, didactic grimace, but would—overcome with saintly trembling—immediately begin to scream and groan, maybe even fall on his knees! Instead of fleeing from immaturity and quarantining himself in a refined milieu, he would understand that a truly universal style is one that can take in its loving embrace the most pitifully unevolved of creatures. This would end by leading you to a form of art so rich in inspiration that you would all become en masse the most powerful, most incomparable geniuses!

But for the serious literary youth of Canada—and even more so for the esteemed elders of "Can-Lit"—Gombrowicz's message requires no inversion. If there is one thing I could say to all Canadian writers (the young ones who write about smoking weed; the old ones who write about the tragedy of old age), it is that there is a stupid, pimply pre-teen on your back (he's wearing a beanie, holding a lollipop, and eating a hotdog!) and that you absolutely must recognize his existence, because as it stands he is beating you to death!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)